In our last installment we looked at the validity of medical claims based on the source of the claim, whether there is cited research, whether the research was published in a peer-reviewed journal, and whether the authors had any conflicts of interest. Let’s assume you are researching the effectiveness of drinking beet juice to improve your running. A friend shares a link to an article on Facebook. The article quotes and references some research studies one of which was published in the peer-reviewed journal Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism . You search for and find the original research article on pubmed.gov. So far you are doing good, the article’s author referenced a research study to back up their claims, the research was published in a peer-reviewed journal, and you can read the abstract online. Now, how do you know if this study is any good? You need to determine what type of study was done and how much evidence that type of study imparts to the research question posed.

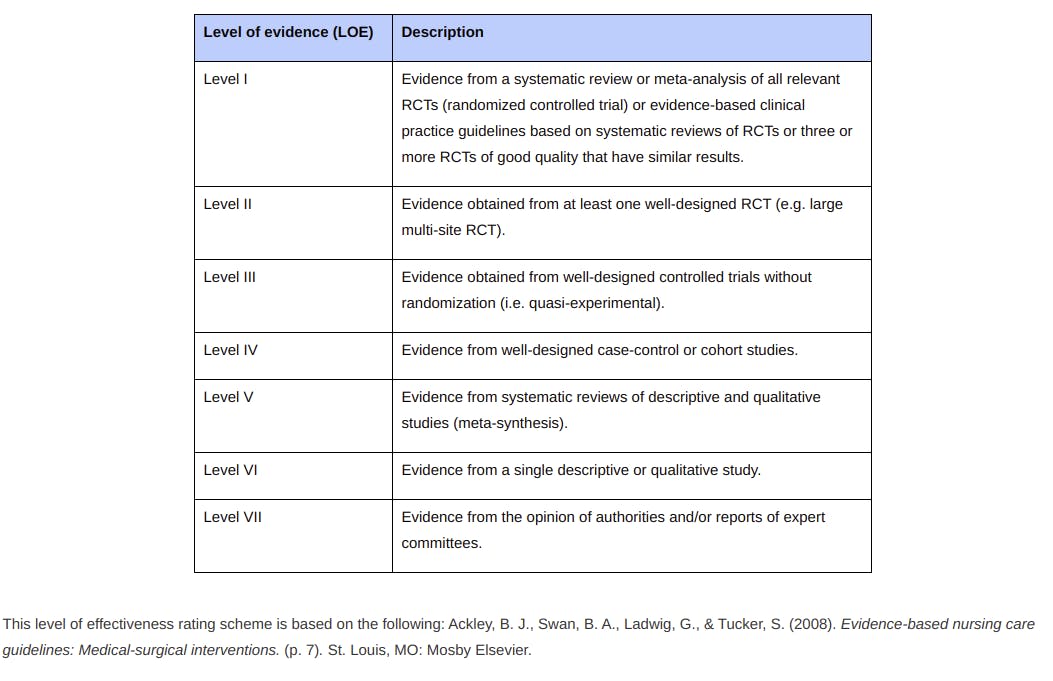

Levels of evidence (sometimes called hierarchy of evidence) are assigned to studies based on the methodological design quality, validity, and applicability to patient care. Here’s a chart describing the basic types:

You should always search for studies with the highest level of evidence, i.e. meta-analyses or systemic reviews that analyze many, many randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) to look for consistent results across large numbers of subjects and conditions. A randomized, controlled trial (RCT) is, according to Wikipedia: “a type of scientific (often medical) experiment that aims to reduce certain sources of bias when testing the effectiveness of new treatments; this is accomplished by randomly allocating subjects to two or more groups, treating them differently, and then comparing them with respect to a measured response. One group—the experimental group—receives the intervention being assessed, while the other—usually called the control group—receives an alternative treatment, such as a placebo or no intervention. “

Level 1 evidence would be the “gold standard” upon which we can make some good medical conclusions regarding our research question. Level 2 evidence is also very persuasive in our decisions to implement new medical treatments based on research findings. Level 3 and below may provide useful information on trends and indications for future research. Our beet juice study appears to be level 3 – placebo controlled, but not randomized because there were only 14 subjects who performed with both beet juice and without beet juice (i.e. a crossover study.) Therefore, you may not want to rush out and buy a huge jug of beet juice to chug before your runs just yet – but the research is intriguing.

They key words you want to look for when reading about scientific research in the mainstream media or on social media are the words “meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.” This means that a number of RCTs have been pooled together and analyzed to provide Level 1 evidence. Lower levels of evidence may be good starting points for new directions in research. For example, if a coach writes an article about how she has noticed her runners performing better with beet juice supplements that may qualify as an expert’s opinion (Level VII.) It could be an accurate description of her experiences but may also be biased by the coach’s desire to sell beet root supplements. She may want to help athletes avoid the temptation of illegal sports-enhancing drugs or she may just want to improve her notoriety in the running community. A RCT on the use of beet juice designed to avoid these biases would help us see if beets really do have a physiological effect on running.

No research study methodology is perfect. That’s why research is published, so it can be carefully reviewed by experts and the general public for any flaws, mistakes, or biases that could impact the author’s conclusions. When flaws are identified, new research studies aim to fix those problems and glean further information on the question. Thus, the scientific method is an iterative process where we gradually gather more and more information on a subject to clarify our understanding and produce better and better medical treatments. Yes, sometimes we get it wrong. It’s always important to challenge established conventions when new evidence comes to light. But it’s equally important to understand that new and unusual claims demand a high degree of scrutiny. Learn as much as you can about science and its methods, and you will be able to make better, more informed decisions on your own.

If you don’t have the time or interest to become adept at evaluating research, you may want to search out expert opinions you can trust. How do you know if an “expert” is trustworthy? How can you avoid getting scammed by disreputable fakes? That will be the topic of the next installment in this series.

If you’d like to experience the difference evidence-based, hour-long, physical therapy sessions can make resolving your pain or healing from injury, call OrthoSport Hawaii at 808.373.3555 for more information on scheduling a free online or in-person consult.